Francesco Griffo da Bologna

Biography by Paolo Tinti

The early years and his work in Padua (circa 1450 – 1480)

Francesco Griffo, son of the goldsmith and engraver Cesare, was probably born in Bologna or in the countryside surrounding the city in the mid-fifteenth century. During the nineteenth century it was established that the printer Francesco da Bologna and the goldsmith, engraver, coiner and painter Francesco Raibolini, called ‘Francia’, who had been considered the same person, were as a matter of fact two different persons.

Today few documents are left to recreate the life and the activity of one the protagonists of book history. It is highly likely that Griffo undertook the career of engraver of printing types (‘punchcutter’) and typefounder for the printers of Bologna, famous for the typographical elegance of their books. However, he soon left his home town, moving to Padua where he lived at least from June 1476 (Rigoni 1934 p. 39). Here, according to G. Mardersteig, during the years 1474 – 1480 he designed and cut two series of punches – modelled on the types of Nicolas Jenson of 1470 – for Pierre Maufer, who hired Griffo for the Roman type of De bello iudaico (Verona, 1480, IGI 5388). Griffo lived in Padua together with his brother Michele at least until 25 January 1480, as proven by an unpublished document with which he tried to recover a long-term debt from Andrea Testa of Padua, his sister’s husband.

Venice and the collaboration with Aldus Manutius (circa 1494 -1502)

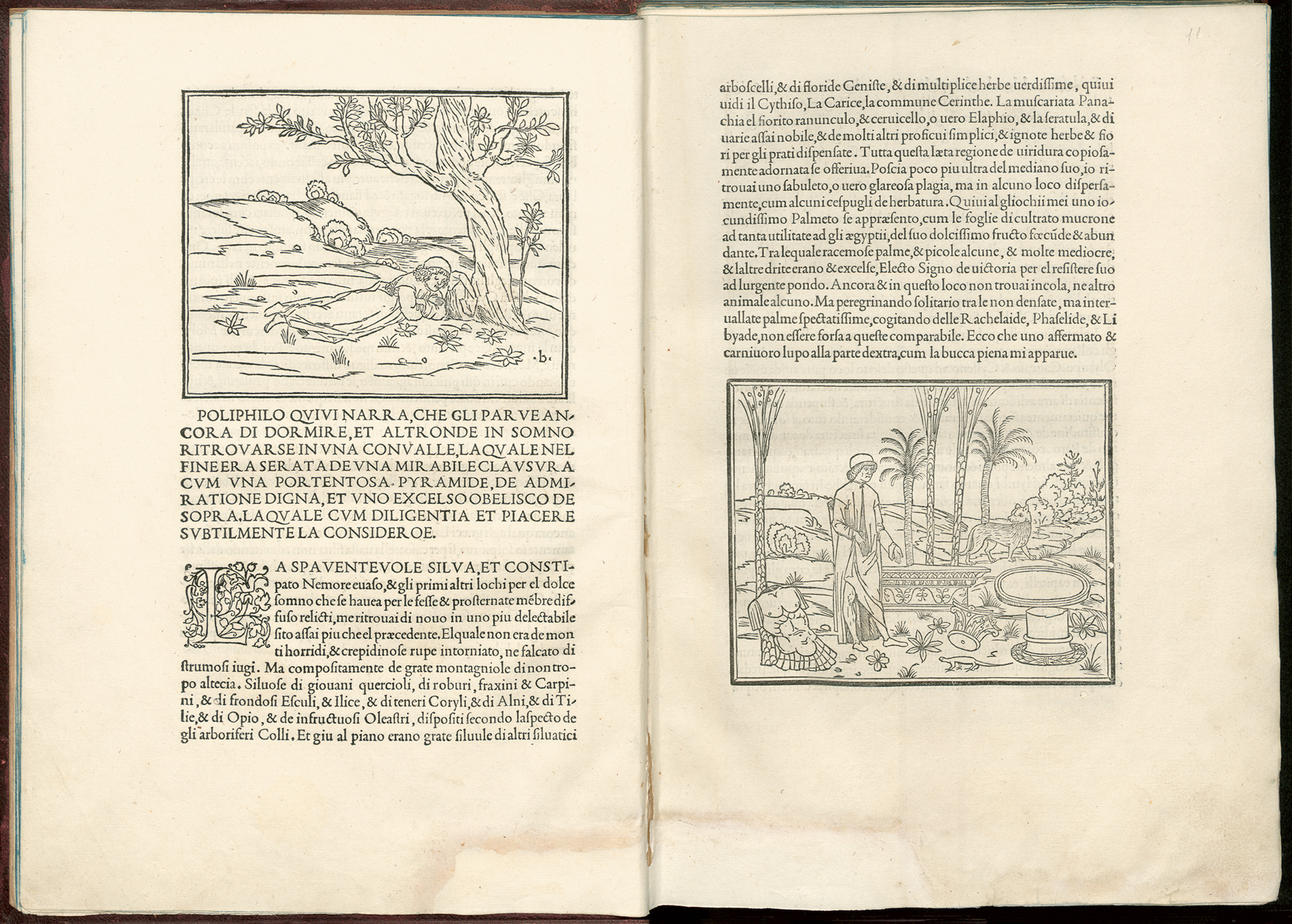

Already from the mid 1470s, Griffo probably had professional connections with Venice, where his experience and expertise allowed him to stand out in a ‘marketplace’ that was of supreme importance for fifteenth-century printing and publishing and was characterized by a high degree of specialization and competition. We do not know what other printing firms Griffo worked for in Venice until the early 1490s. However, it is certain that the ‘Franciscus de Bononia quondam Caesaris aurifex’, hired in 1475 by the merchant Johan Rauchfass to copy Jenson’s roman type, really was Griffo. According to G. Mardersteig, Griffo cut two series of Roman types for the workshop of the brothers Giovanni and Gregorio De Gregori between 1483-1487 (Horace, IGI 4881 and Valerius Maximus, IGI 10068). However, following his recent research, R. Olocco affirms that this type is none other than the already mentioned Roman type of Jenson. Thus it is possible that our Bolognese punchcutter also turned to Andrea Torresani of Asolo, who in 1487 had acquired the typographic material of Jenson, who had died around 1480. In March 1495 Torresani established a company with Pierfrancesco Barbarigo and Aldus Manutius and in 1494 or 1495 Griffo, ‘maybe the most important figure’ of the company of Manutius (Lowry 2000, p. 119), started working with Aldus and cut many different series of types for him, drawing inspiration from classical and imperial Roman inscriptions and, at the same time, from contemporary calligraphers. The letterforms of his types were unsurpassed for many centuries, culminating in De Aetna by Pietro Bembo (dated February 1495 more Veneto, but 1496) and in the princeps of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499).

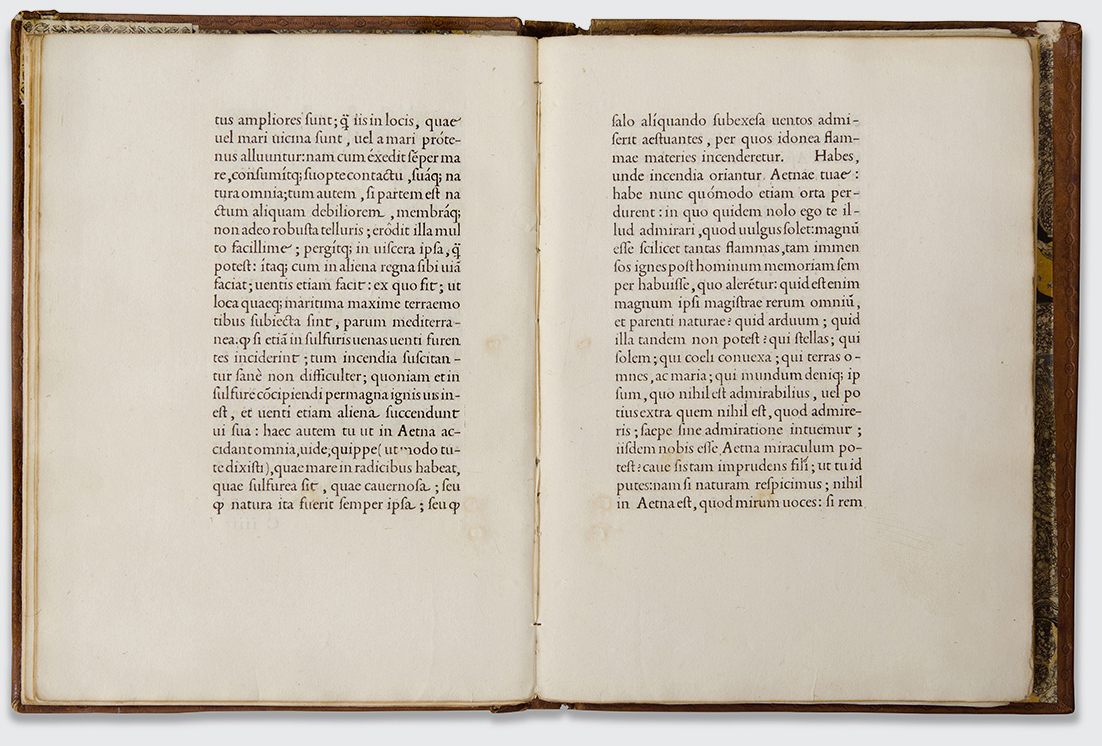

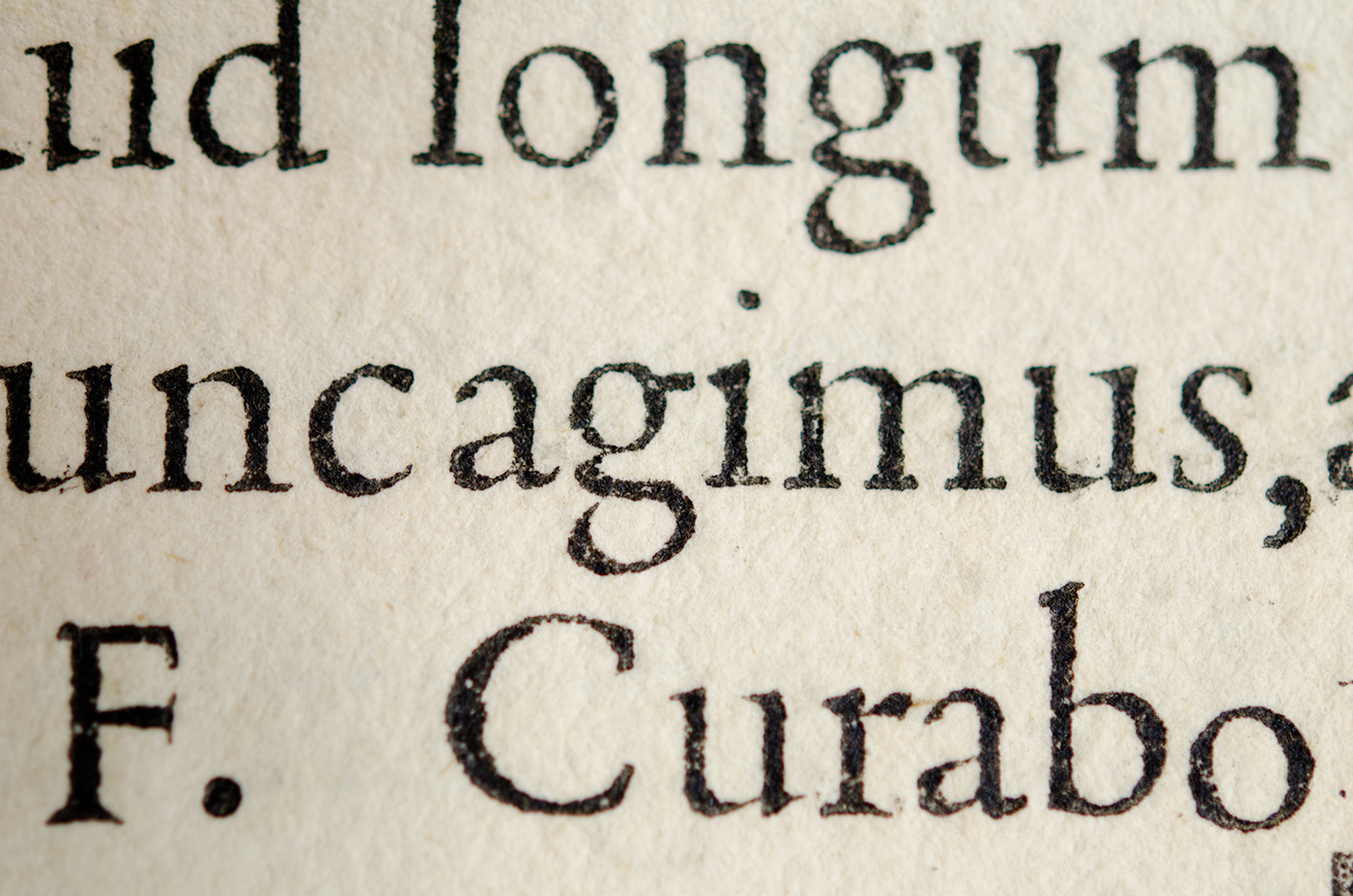

Roman round types

Griffo created five Roman types for Manutius: the ‘Gaza’ (for Introductivae grammatices of December 1495, R1a 110) and the R1 108 used for the Latin paratext of Erotemata by C. Lascaris (28 February 1495, more Veneto: 1496). Two similar Romans (R2 81 and R2a 82) for the Latin text of the Greek Aristotle and for the Gaza of 1499; the ‘Gaza’ Roman (R3 83, 1496-97), the ‘Bembo’ Roman (used in the above mentioned De Aetna, R4 114), which was later adapted in two versions that can be found in Politian and in Hypnerotomachia Poliphili; and finally the Roman called ‘Leoniceno’ (R5 87, June 1497), famous for the calligraphic inclination, with long and sinuous shapes. For the uppercase Roman of the Hypnerotomachia Griffo adopted a 1:9 ratio of the width to the height of stems of uppercase letters, in accordance with the manuals on Roman letters of that period (L. Pacioli, F. Torniello and G.B. Verini). The great skill evident in the design and casting of these types (the so-called ‘nove forme de antiqui carattheri’, as Griffo wrote a few years later in the preface to his first Bologna edition) led, in the case of the De Aetna, to the choice of creating different versions of the same letter, in an attempt to reproduce as much as possible some of the variety of handwriting.

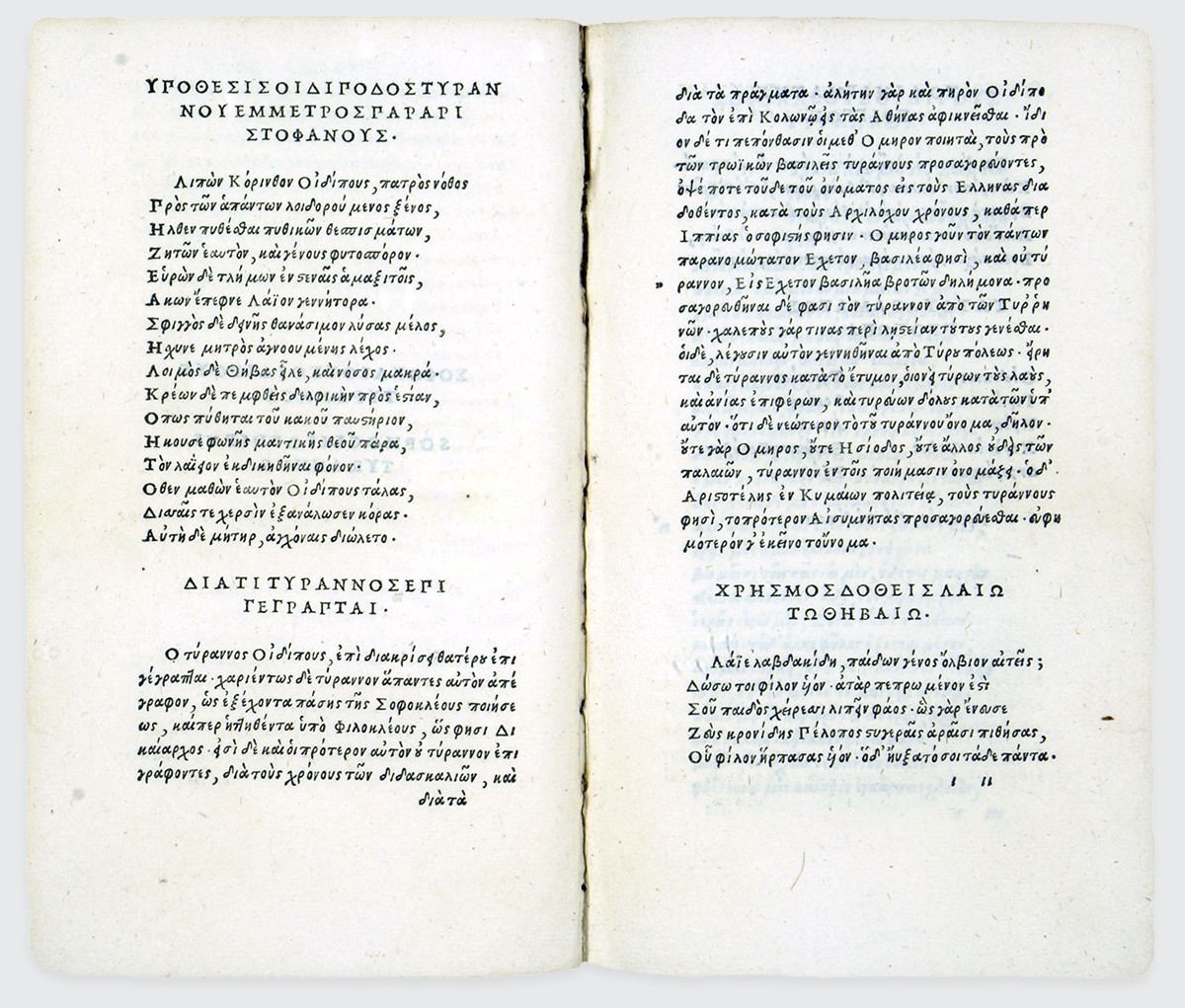

Greek types

During the early years of his collaboration with Aldus Griffo cut Greek types with letterforms inspired by the writing of Immanuel Rhusotas, a Byzantine scholar who came to Venice in 1465. Griffo made four different versions for Aldus and the first dated Aldine Greek appeared in the Alphabetum Graecum (March 1495), a text by Aristotle of November of the same year, the first volume of the great Greek editions in the original language. Greek types with complexities such as breathings and accents as well as numerous ligatures of nexuses or diphthongs, were the best example of Griffo’s extraordinary technical skills. The last version of the Greek alphabet cut by Griffo was italic; it was Greek 4, used in Sophocles’s tragedies, published by Aldus in August 1502. In his Bologna edition of Petrarch’s Canzoniere of 1516 Griffo himself refers to his Latin, Greek and Hebrew types: ‘havendo pria li greci et latini carattheri ad Aldo Manuzio R.[omano] fabricato’).

Sofocle, Aldus Manutius, Venice 1502. BUB, Raro B. 57, 2 cc. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna.

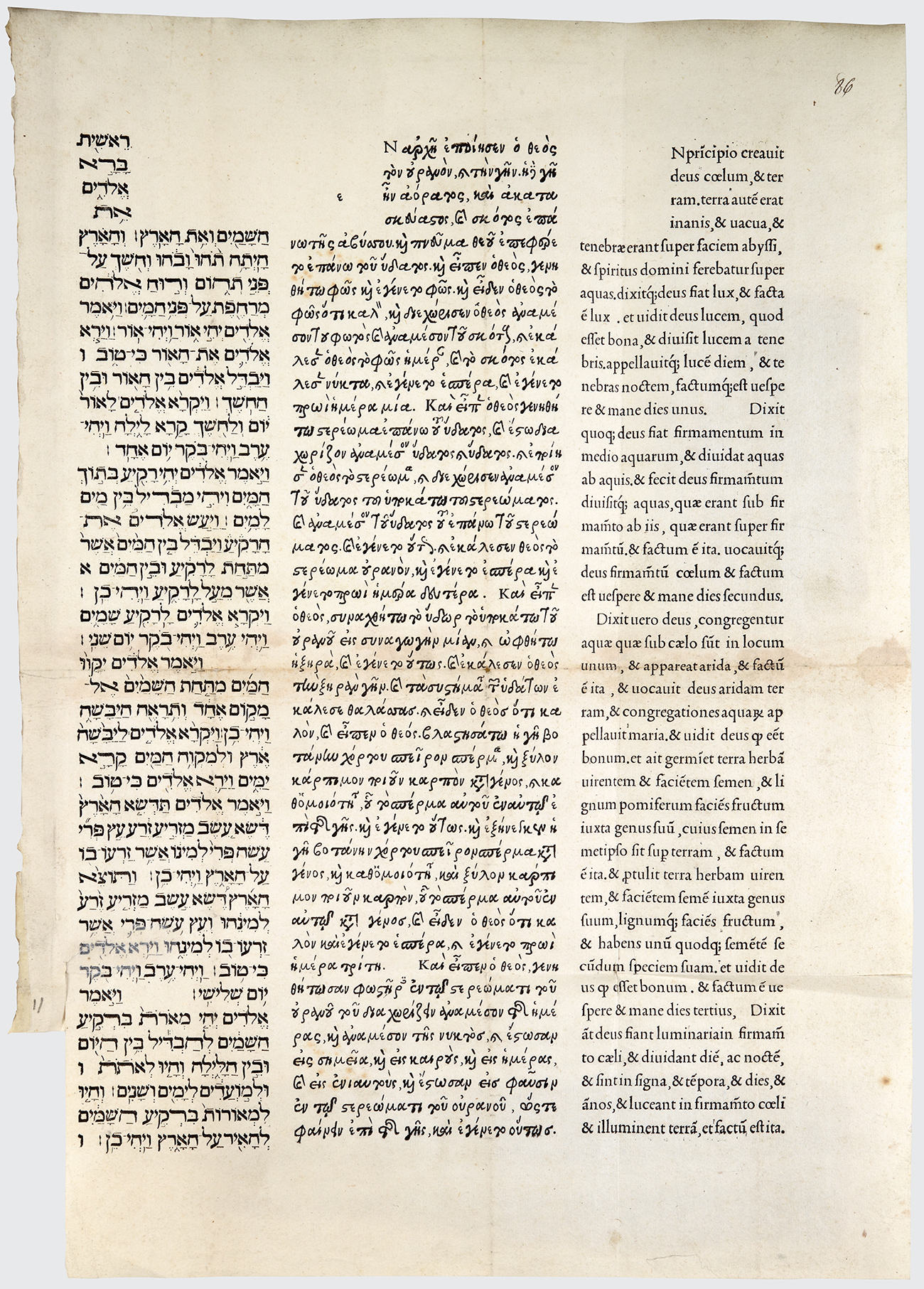

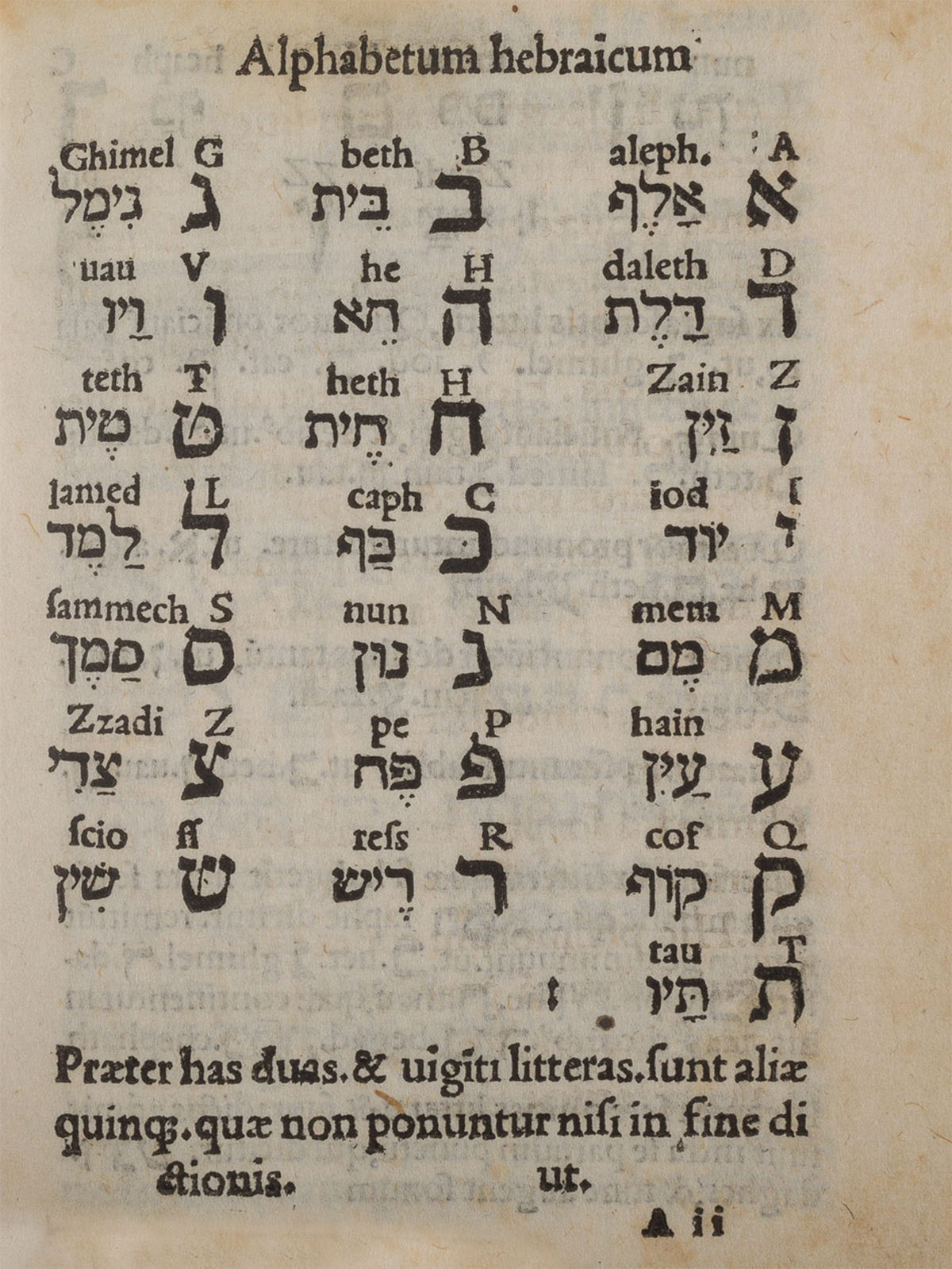

Hebrew type and the collaboration with Girolamo Soncino for the polyglot Bible of Aldus

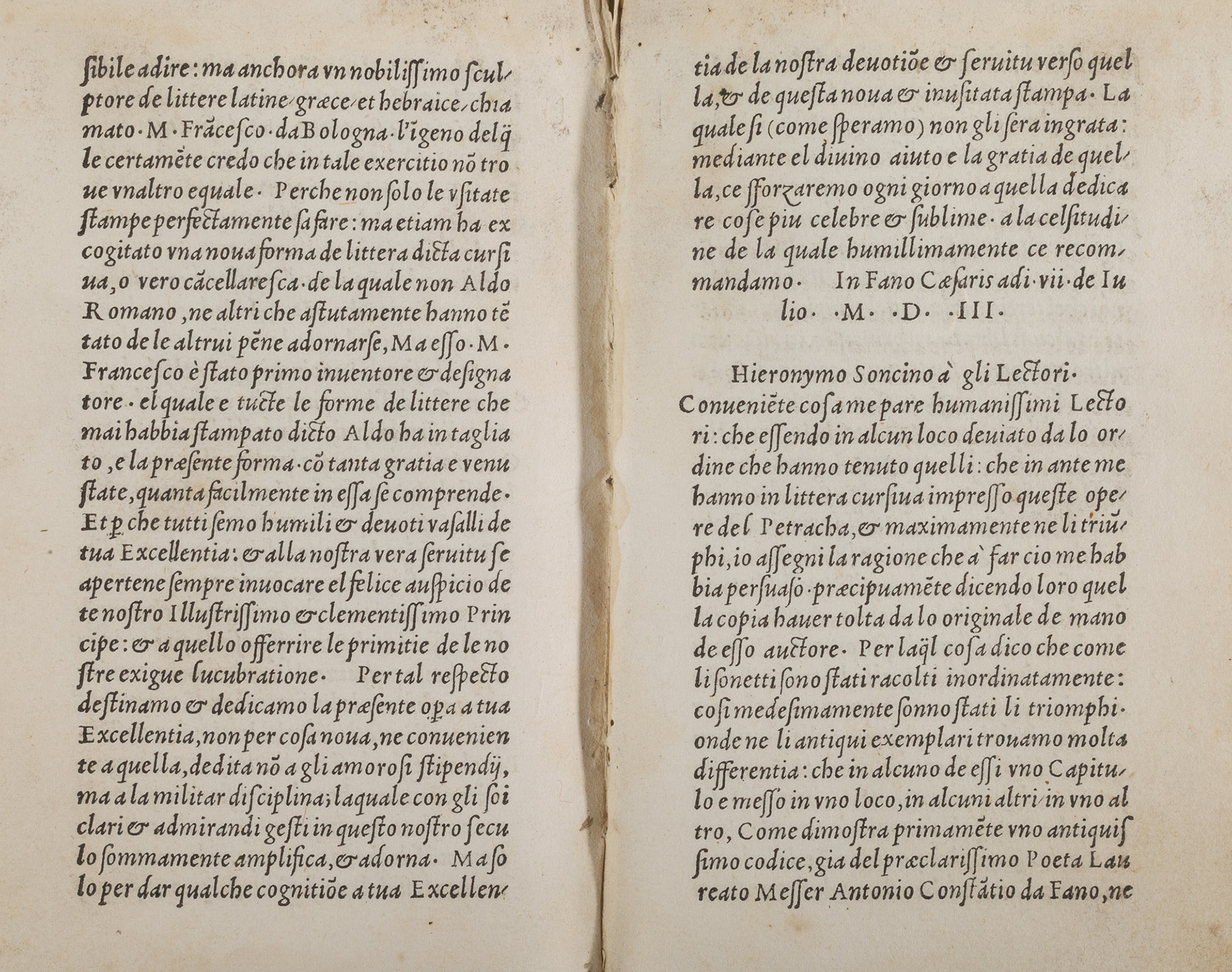

In the dedication to Cesare Sforza in his 1503 Petrarch, the publisher and printer Soncino extolled the skills of Griffo, who had just left the company of Manutius and moved to Fano. Soncino defined him as a ‘nobilissimo sculptore de littere, graece et hebraice’ (Manzoni 1886, pt. 2, pp. 26-28). It is highly likely that the Hebrew types of the Introductio ad litteras Hebraicas, published in Aldus Manutius’s Institutiones of 1501 – the first Venetian edition in Hebrew type – were cut by Griffo. Furthermore, it is also very likely that Soncino wrote the text of the Introductio. Named after the town of Soncino, this itinerant Jewish printer and publisher had come to Venice from Brescia to work with Aldus on the polyglot Bible, of which only a proof has survived.

Polyglot Bible, Aldus Manutius, 1498-1501. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Introductio at litera ebraicas, Girolamo Soncino, Fano 1510. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Comunale Federiciana di Fano, photo by Alex Cavuoto e Vanja Macovaz.

The invention of italic type

Griffo must have been stimulated by the lively cosmopolitan and cultivated environment of Venice. Aldus was the creator of the new, modern book and his public was represented by humanists, philologists, experts of classical and ancient languages, miniaturists and calligraphers and avid readers (both men and women). Griffo continued to cut new types for him and one of these was particularly significant. It was inspired by the cursive writing that was common both in the chanceries of the period and in the calligraphy of Bartolomeo Sanvito, copyist for Pietro Bembo and miniaturist of the Aldine books. Slightly inclined to the right, this first italic type was used by Aldus to set a series of classics – without commentaries – in a small octavo format, that he called enchiridia. These books could be easily held in the hand and they opened up an entirely new approach to reading. Following an appearance in the Letters of Saint Catherine of Siena (September 1500), Aldus used the italic type again in his Bucolica of 1501 and it is in the incipit of this book that he publicly acknowledges and praises the work of his designer of types (In grammatoglyptae laudem), ‘the highly skilled hands of Francesco da Bologna, punchcutter of Greek and Latin types’. Aldus, who never again mentioned Griffo in his editions, was well aware of the innovative potential of the italic type and applied for a ten-year privilege for their exclusive use. On 23 March 1501 the Senate of the Venetian Republic granted the privilege and on 14 November 1502 Aldus protected the entire production of his engraver’s types with a provision of the Doge. Thus Griffo lost any bargaining power with the publishers and printers within the state of Venice (Fletcher 1988). Disappointed by how he had been exploited, Griffo left Venice in the winter of 1502.

The first italic type cut by Francesco Griffo. Letters of Saint Catherine of Siena, Aldus Manutius, Venice 1500. BUB, A.V.KK.XII.1. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna.

The second italic type engraved by Francesco Griffo. Opere volgari di Messer Francesco Petrarca, Girolamo Soncino, Fano 1503. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Federiciana di Fano.

The period in Fano, with Soncino and work in the papal provinces

Griffo moved to Fano where he worked with Soncino, who had also quarelled with Aldus and who had left Venice in 1501. During Soncino’s years in Fano from 1502-1507, Griffo designed a second italic type with fewer ligatures for a series in octavo which Soncino had planned with the humanist Lorenzo Astemio. Following this, Griffo went into a partnership with Girolamo and Bernardino Giolito de’ Ferrari, called Stagnino, as proven by an unpublished document of 3 August 1503. Another document dated 31 August 1503 tells us that together with Stagnino, he later granted power of attorney to the printer Giovanni Ragazzo in order to protect his investment. From 1511-1513 he worked for Ottaviano Petrucci of Fossombrone and for Stagnino of Venice, settling in Perugia where he lived in 1512, as indicated by certain documents from January and August. In the same year he was paid 20 ducats by Stagnino, possibly for types used for a work by Dante that he had cut in November. According to Montecchi, Griffo designed the punches used for the first book printed in Arabic type, published in Fano in September 1514 by De Gregori (Montecchi 2007, pp. 77-78).

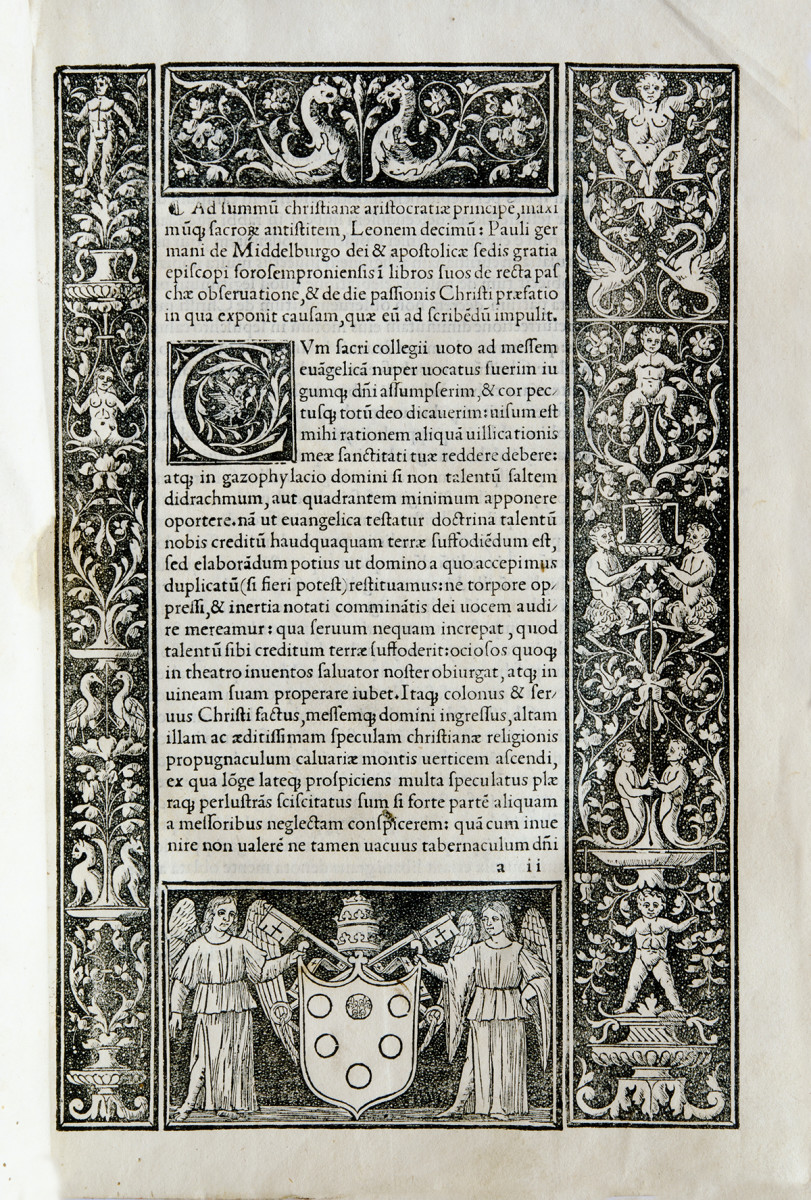

Paulus de Middelburgo, Paulina de recta Paschae, Fossombrone, per Octavianum Petrutium, 1513, 8 luglio. Courtesy of the Biblioteca del Capitolo Metropolitano di Milano.

Griffo’s work as printer and publisher in Bologna, 1516-1517

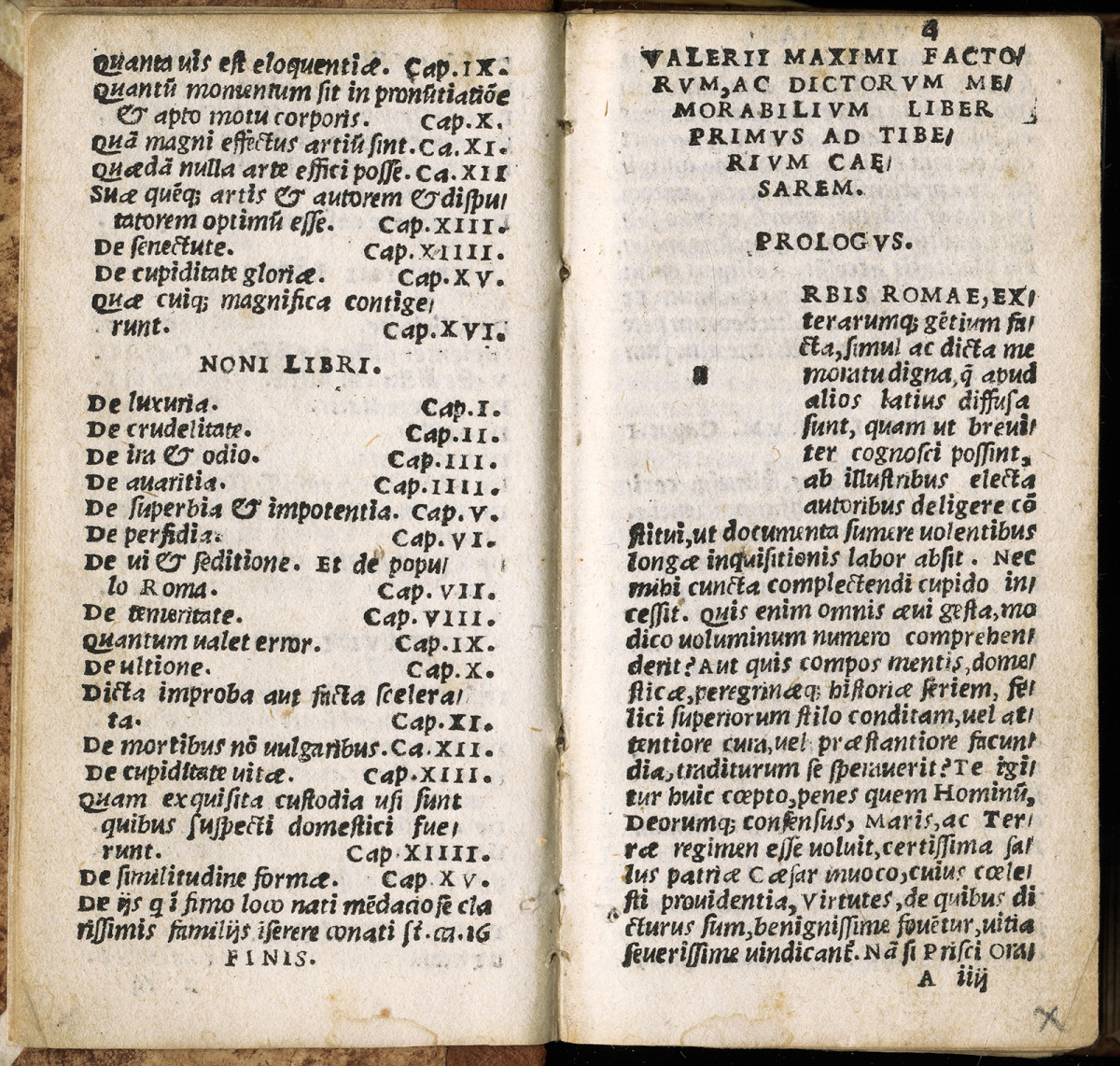

By the autumn of 1516 Griffo was back in Bologna, where he started working as a publisher. Fully confident in his punchcutting abilities, he applied his skills to the publication of a series of octavo Latin and vernacular texts. Already famous to readers all over Europe, thanks to Aldus and Soncino, Griffo set these books in another, very small, italic type. The first published work was Petrarch’s Canzonier et Triomphi (20 September 1516). In the same year Griffo published four other works: Archadia by I. Sannazaro, Asolani by Bembo, Labirinto d’amore by Boccaccio and Epistolae familiares by Cicero, the rarest of his publications, mentioned, but never actually seen – not even by the most important bibliographers. The Latin subseries was integrated by Dictorum et factorum memorabilium by Valerius Maximus (dated 24 January 1517). Because it is set in the same Italic type, a page of a graduation thesis that was disputed in Bologna on 30 November 1516 has also been attributed to Griffo (Serra Zanetti 1959, pp. 189-190). It is highly likely that Griffo died in Bologna in 1518, or in any case, not later than October 1519. He may have been executed after the trial for the murder of his son-in-law, Cristoforo De Risia, husband of his daughter Caterina. According to the court proceedings Griffo struck his son-in-law on the head with a steel bar during a clash that occurred in the house shared by both, in the parish of San Giuliano.

The third italic type cut by Francesco Griffo. Il Canzoniere, del Petrarca, Francesco Griffo, Bologna 1516. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio di Bologna.